Visual and Digital Poetry, Week Four

Poetry must realize that reading is changing—the reading brain is changing (it’s not so long ago Socrates feared what the printed world would do to our intellectual life). Reading now gleans information at light speed—breaking news updates, Google headlines, e-mails, tweets, incessant chat and text messages. . . Where does this deluge of text and moving image lead us? – Crag Hill, The Last Vispo

VISUAL POETRY - WEEK FOUR

What does it leave us? Look to how a visual poem can be read. That act—those transactions between/within reader, word, and image—instructs us on how to gather meaning from the intensifying syntactic flashes of our internal and external world." – Crag Hill, The Last Vispo

Coda

Reading a visual poem takes a minimum of three steps:

1) Read the entire page/space at once. The visual poem is designed to first be read whole (unlike most poems on the page chained to left to right, top to bottom regimens).

2) Read the parts of the whole. Consider their position on the page/in space, their relationships to other parts. Much that happens in a visual poem happens here.

3) Read the full poem again at the same time reading its elements as they combine and re-combine to create the whole.

-Crag Hill, The Last Vispo

Ovonovelo

The geometric-isomorphic poem, on the other hand, would be arranged more like an ideogram, so as to achieve “simultaneity in space” and discard any reside of “syntactical ordering.”

Constructing an Avant-Garde: Art in Brazil, 1949-1979 By Sérgio B. Martins

What was once an exercise in matching sound to sense, the visual poet is charged with matching sight to sense. It does not preclude text rather it embraces text in a variety of alternative ways that the normal practice of linear mode of reading -Harold Bloom, How to Read and Why

READINGS

Augusto de Campos

Augusto de Campos

Décio Pignatari

“He was 85 and lived in Sao Paulo. With [brothers] Augusto and Haroldo de Campos he edited the magazne Noigandres e Invenção and they together wrote Teoria da Poesia Concreta (1965).” That’s him up top, center, circa 1950.

There are films/visual poems and other resources up at UBUWEB, including a paper by Mary Ellen Solt on the Brazilian concrete poets. A bit of history:

In 1952, the year Gomringer wrote his first finished constellation “avenidas,” three poets in São Paulo, Brazil–Haroldo de Campos, Augusto de Campos and Decio Pignatari–formed a group for which they took the name Noigandres from Ezra Pound’s Cantos. In Canto XX, coming upon the word in the works of Arnaut Daniel, the Provencal troubadour, old Levy exclaimed: “Noigandres, eh, noigandres / Now what the DEFFIL can that mean!” This puzzling word suited the purposes of the three Brazilian poets very well; for they were working to define a new formal concept. The name noigandres was both related to the world heritage of poems and impossible for the literary experts to define. They began publishing a magazine of the same name, and within the year had begun correspondence with Pound and had established contact with concrete painters and sculptors in São Paulo and with musicians of the avant-garde.

Décio Pignatari

boba coca cola

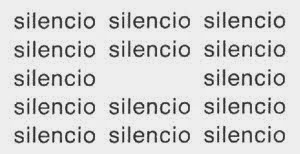

Silencio (1954) by Eugen Gomringer

Eugen Gomringer

Augusto de Campos

Eugen Gomringer

Eugen Grominger